This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Organisational change – On language and culture… (2 of 5)

06 June 2022

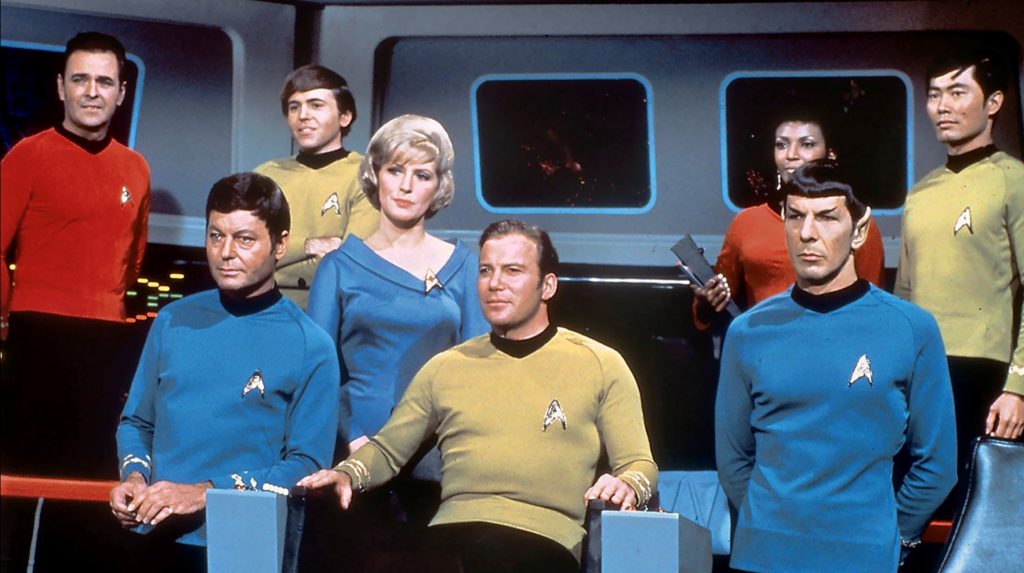

In the Star Trek episode “The Menagerie” aliens created their own new world through a mental force known as the Reality Distortion Field

Part two of a series of thought pieces by Ben Story, COO of SDCL

The Reality Distortion Field was “Steve Jobs’ ability to convince himself, and others around him, to believe almost anything with a mix of charm, charisma, bravado, hyperbole, marketing, appeasement and persistence. It was said to distort his co-workers’ sense of proportion and scales of difficulties and to make them believe that whatever impossible task he had at hand was possible.” (1)

The Reality Distortion Field was a term used by Bud Tribble at Apple Computer in 1981 to describe co-founder Steve Jobs. Few of us have the ability to communicate like Jobs, but all of us should appreciate the power and impact of the language we use. Language is how we express our culture. It is how we communicate our beliefs and values. It helps foster feelings of identity and community. As Ludwig Wittgenstein, the philosopher, said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

The tech industry has brilliantly institutionalised the notion of change, which it has rebranded “pivoting”. Pivoting cleverly portrays momentum and choice. For small organisations, it makes sense; however, telling workers on the shop floor of a 1960s factory in Cologne or Milwaukee or Scunthorpe that they need to “pivot” is likely to illicit a predictable response…

Pivoting deliberately contrasts positively with larger, established organisations. They have adopted their own rebranding, relabelling change programmes as “transformations”. Searching “Transformation” on McKinsey’s website generated 18,528 results versus 18,529 for “Strategy”.(2) I presume that this collective decision to up the ante is intended to demonstrate boldness and tackle the forces of resistance, but there is a danger that such language increases the level of toxicity. There is also the risk of devaluing language by over-use and familiarisation.

More recently, the term “Agile” has grown in prominence. This concept has been borrowed from the tech industry. Agility is a fine characteristic for any organisation – plus it implies that change is innate – but as a rallying cry for change it is passive and vague. (“Let agility commence!”) I also wonder how agility will fair alongside growing demands for resilience and sustainability. I am inspired by Nike’s entreaty to “Just Do It”.

Organisations should also be mindful of how they describe themselves. As a boy, I remember being on the school bus making its way along Grosvenor Road in Tunbridge Wells and frequently puzzling at a travel agent called – to the best of my recollection – East-West Travel. “Why would you brand your business East-West Travel?”, I idly wondered. Years later, I popped in to the travel agent and enquired, “Do you travel north and south?”. “Of course!”, they replied.

When I joined Rolls-Royce, it was often referred to as an “engineering company”. The new leadership team championed Rolls-Royce as an “industrial technology group”. By changing the cognitive framing, we encouraged references to the tech industry, and all the expectations that this encompasses. At Citi, some of my colleagues continued to refer to its UK Investment Banking business as “Schroders”, even though more than a decade had passed since Schroders had been acquired by Citi. Whatever the merits of the brand, the continued references to Schroders made it hard to integrate the acquisition and realise its full potential.

Technology companies have been especially thoughtful about maintaining a change capability as they grow. For example, Amazon exhorts its “Day 1” mentality, seeking to retain the proximity, intimacy and responsiveness to customers that it had as a start-up in 1994.(3) (Amazon now has over 1.6 million employees.) Similarly, Netflix explicitly seeks to avoid excessive managerialism through a focus on talent. Reed Hastings’ famous slide deck on culture sets out that “Growth Increases Complexity” and states that Netflix will seek to “grow with ever more High Performance People…Then you can continue to run informally with self-discipline”.(4)

The language and culture of change needs to build on an organisation’s strengths and goodwill, however compromised these may be. Before joining the UK Civil Service, Dominic Cummings publicly set out his views on its culture: “The people who are promoted tend to be the people who protect the system and don’t rock the boat…A lot of young people who care and work hard are often disillusioned quite quickly and leave, and the ones who play the system and focus on personal goals and not the public interest also tend to be the ones who are promoted”. Later, when Cummings was appointed Chief Adviser to the UK Prime Minister, it is unlikely that his earlier comments helped his quest “to make rapid progress with long-term problems”.(5)

(1) See Reality Distortion Field on Wikipedia.

(2) Taken from the McKinsey & Company website on 26th April 2022.

(3) See Elements of Amazon’s Day 1 Culture, AWS Executive Insights by Daniel Slater, Worldwide Lead, Culture of Innovation at AWS.

(4) See Freedom and Responsibility Culture by Reed Hastings.

(5) See ‘Two hands are a lot’ — we’re hiring data scientists, project managers, policy experts, assorted weirdos… by Dominic Cummins.